Chinese Words That Don’t Exist in English

Introduction: The Challenge of Translating Chinese Concepts

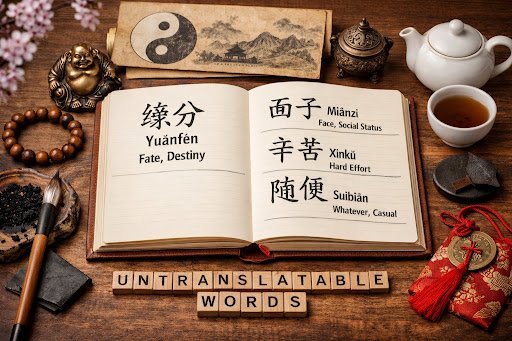

Students who learn Chinese online or work with an online Chinese teacher quickly discover that some Chinese words simply do not translate easily into English. These terms are deeply rooted in Chinese culture and often lack direct equivalents in Western languages. Understanding them requires more than vocabulary memorization—it requires cultural insight.

Why Some Chinese Words Are Untranslatable

The phenomenon of untranslatable words exists in every language, but Chinese offers particularly rich examples because of the fundamental differences between Chinese and Western cultures. Chinese characters function as ideograms, meaning each character represents a concept rather than just a phonetic sound. When these words are translated into English, they often require long explanations that still fail to capture their full cultural depth and emotional nuance.

A Deeper Sense of Fate

One of the most significant untranslatable concepts is 缘分 (yuánfèn). While it is often translated as “fate” or “destiny,” the meaning goes much deeper. Rooted in Buddhist philosophy, yuánfèn refers to the invisible force that governs relationships and encounters between people. It suggests that certain connections are meant to happen, beyond individual control or coincidence.

This idea applies to romantic relationships, friendships, and even chance meetings. When two people meet and form a meaningful bond, Chinese speakers may attribute it to yuánfèn, acknowledging that some relationships are predestined. The term carries emotional and spiritual weight that the English words “fate” or “destiny” do not fully convey.

The Importance of Social Reputation

Another culturally significant concept is 面子 (miànzi), often translated as “face.” However, miànzi goes far beyond physical appearance. It refers to social prestige, dignity, and public reputation as perceived by one’s social circle.

In Chinese culture, maintaining miànzi is extremely important, and losing it can be considered a serious social setback. A well-known proverb states that men live for face as trees grow for bark, emphasizing its importance. The management of miànzi influences business negotiations, family relationships, and daily social interactions.

Closely related is 给面子 (gěi miànzi), meaning “to give face.” This refers to showing respect for someone’s status and feelings through thoughtful actions. Gestures such as offering public praise, giving an appropriate gift, or observing proper seating arrangements at formal events are ways of giving face.

Recognizing Hard Effort

The expression 辛苦 (xīnkǔ) literally translates to “bitter work,” yet its meaning extends beyond simply saying “hard work.” It acknowledges the emotional and physical effort someone has invested in a task.

When someone says xīnkǔ, they are not only recognizing the labor involved but also the sacrifice and perseverance behind it. It is commonly used to thank someone, expressing appreciation for the challenges they have endured. This emotional nuance makes it more meaningful than the straightforward English equivalent.

A Word Shaped by Context

The term 随便 (suíbiàn) presents unique translation challenges because its meaning depends heavily on context. It can mean “casual,” “flexible,” “whatever works,” or “anything is fine.”

When used in response to a question about preferences, suíbiàn may indicate genuine flexibility or indifference. However, in certain situations—especially during disagreements—it can carry a passive-aggressive tone, implying that the speaker no longer wishes to argue. This range of meanings makes it difficult to translate consistently into a single English word.

Conclusion: Teaching Cultural Meaning Beyond Direct Translation

Chinese language institutions such as GoEast Mandarin in Shanghai often emphasize understanding these words through context rather than direct translation. Through interactive lessons and practical activities, students learn how these terms function in real-life communication. This approach allows learners to grasp not just vocabulary, but the cultural mindset behind each expression.

Chinese culture has developed under the influence of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, creating philosophical foundations that differ significantly from Western traditions. Collectivist social values also shape how individuals relate to the group, contrasting with Western individualism.

The existence of untranslatable words highlights how language reflects and shapes worldview. By learning these culturally embedded terms, students gain deeper insight into Chinese society and the values that guide everyday interactions.